This is the second part of our interview with Anna Cantor, a coach and consultant for those caring for a family member who has dementia. Because the disease manifests itself in so many ways, individualized coaching is often recommended. In the conversation below, Anna provides practical tips that can hopefully help you in your caregiving journey.

Ben: What do you think are some of the biggest misconceptions people have as they begin their journey as a dementia care partner?

Anna: A big concern is what the disease is going to look like in the future. Often doctors and other professionals will be really vague about exactly what the future holds because they don't want to be held accountable for something that might turn out to be out of the ordinary. I remember asking my mom's doctor to actually explain how somebody with Alzheimer's passes away who's not 95 and doesn't fall and break their hip, for example. Her condition has kind of been stagnant for years. The decline hasn't really changed; she hasn't gotten any better, she hasn't gotten any worse in the past two years, but she's in bed. She doesn't talk. She's fed by a family member. She can't really eat on her own. She's completely immobile and she has tiny spasms all the time. I don't know how and when her disease will progress. But when I started this journey, I had hoped that the journey itself would be more clear and defined. It’s not, and it won’t be. But there are plenty of ways to prepare, regardless of how it progresses.

As a dementia coach, I want to set up my clients so that they are well prepared, and I think one of their concerns is just how to prepare. What do you do first? I help create a roadmap around the disease's progression, but also create that end-of-life roadmap earlier than they think might be necessary. A lot of people understandably don't like to talk about that. But I think it's really important to talk openly about end-of-life planning. Of course, I'm careful and sensitive in how we talk about this.

Ben: It seems like there's just so much that you, as a dementia coach and consultant, can do to help people navigate this journey. I imagine it's easy to fall into information overload. How do you balance the logistical and practical advice you're giving with the emotional?

Anna: I love consulting because it's so individualized. In an hour-long session, I will have a list of logistical things to discuss with the client -- things like contacting an elder law attorney or installing new safety equipment in the home. With some people, this part of the call is very straightforward. Others can be overwhelmed, so we might spend the beginning of the session just talking about how the past week went and I'll collect information at a different pace. But I do try and hold them accountable to the important things that they need to get done. I really recommend meeting weekly.

Over the course of a week so much can happen, and the person with dementia can be so different or they could just be completely the same. So each session is very open and authentic, covering similar ground as one might with a therapist. But what I really like about my service is that I'm available around the clock, especially for somebody who is having a little bit more challenging behavior with a loved one. I have clients message me with challenges; they might not be able to get mom or dad to shower or change clothes, for example. And then I can coach them through that, during the week outside of our sessions, which I think offers a ton of value to people. I can also help with the emotional side as well during these out-of-session messages.

It's so much easier to process things externally. My coaching helps guide people through that process. I want to equip my clients with both the logistical background in planning and navigating long-term care, and pair that with the emotional support. We'll talk through their feelings while also creating an action plan for steps they need to take that week for their care plan. As I tell my clients, your thoughts create your actions.

Ben: Can you give an example of a type of challenge that some of your clients face?

Anna: Often a family member will want to leave the house, unaccompanied, or might be involved in some other unwanted behavior. So we'll dig into the reasons why this might be happening. Do they constantly see something by the front door that makes them want to leave? Are they always trying to put on their shoes and go out the door at five o'clock because that's what they did before they got sick? Did they used to go for a jog? Small changes to an environment can make a big impact. A lot of clients get frustrated about how difficult it might be to communicate with their loved one. But I have to remind them that you're healthy and they are not. So it's on you to improve communication. It's on you to change. They can't change. But we can change how they spend their time, their environment and other stressors that might be around.

Ben: What's the best practice in terms of providing emotional support for a loved one who is not living at home, but is instead at a memory-care or other type of senior-care community? How often should they be visiting? Does it matter if their loved one remembers the visits? What should the main goal be during a visit?

Anna: It's really up to the individual and the family. For me, I originally remained in Seattle because I did not feel comfortable leaving the area and being away from my mom in case something happened. Finally, in 2018, I felt comfortable being away and moved abroad again with my family, but came back a year later. I was at peace with it when we moved. I was at peace with possibly getting that message in the middle of the night that she passed. That never happened, and mom is still alive, and I’m living near her again. So I have this really special time with her now. There's really no right or wrong answer for how to best use this time, but I think what you can do in that moment, to make the visit meaningful to both you and your loved one, should be the goal. There may be some guilt that arises, but like I mentioned before, coaching sessions are for working through that in any capacity needed.

I had one client whose father used to love reading the newspaper. And so they would just sit there and he would have Zoom open and she would read the newspaper. And they would do that for about an hour. Her father might not remember any of the news that day, but he’ll more likely feel satisfied, content, and loved. All of these challenges, and ways to overcome them, are pretty individualized.

Ben: What sort of practical, universal advice can you give to new care partners?

Anna: My best advice is to get a coach. Find someone to talk to. Being a care partner shouldn’t be solely your burden because it's not. Whether that is having a meeting with a therapist or going to a support group once a month, that might be all the support new partners need. There are so many different kinds of resources out there; new care partners just need to be a little proactive and find those resources.

Ben: I remember how difficult it was for us to find the right products -- from clothes to communication devices to activities -- for my grandfather when he had dementia. What products do you recommend to help?

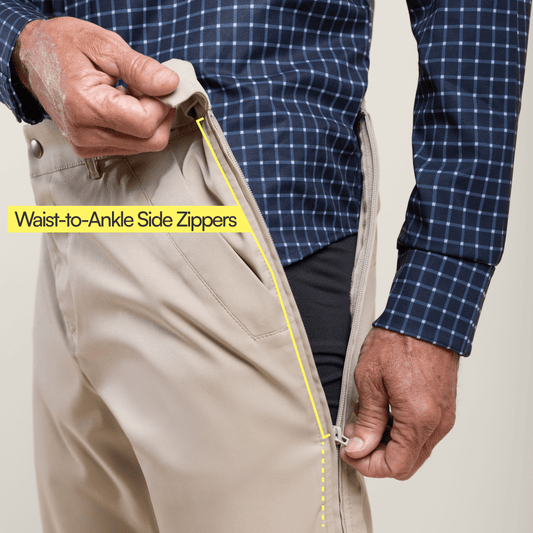

Anna: Helping somebody get dressed can be challenging. It's almost interrogating for them, an invasion of their personal space, when you're trying to pull something over their head. So having long-sleeve zip ups and other clothes that have open backs so they can put on a shirt without having it go over their head is really essential for people with dementia. Also make sure the fabric is soft and lightweight, because they often tense up. Heavy clothes can get tangled and really uncomfortable. My mom has small seizures and her muscles are tense so she needs long sleeves. Keep an eye out for their fingernails and toenails. Some states require podiatrists to come in and cut the nails. I learned that it was safer for my mom to wear long sleeves to reduce the chance that she would scratch herself.

My grandma is still around and she always loves to look nice and be put together. She should be able to wear clothes that still look great on her. I think oftentimes people only think about the function of clothing when it comes to older adults and those with dementia. But the form, the aesthetic, is so important. It helps adults not only feel great, but latch onto aspects of their own identity.

Ben: What do you think of doll therapy? I've seen a lot of people with dementia use dolls as a form of therapy. We carry a couple products in a similar vein, including a product called Companion Pets, which are animatronic dogs and cats. They bark and meow and even have a heartbeat.

Anna: Oh, I love using dolls and products like that. Dementia patients often revert to childhood. Caring for a doll or pet makes them feel like they have a purpose. I think a lot of people with dementia are attached to dolls because they're trying to provide comfort. My mom really reverted back to her childhood and would always call me her sister. Anything that offers that companionship, giving them a sense of purpose, is really great.

Other sensory games or activities are helpful and engaging. One thing that happens with dementia is vision changes. People have to go from having binocular vision to really not having any peripheral vision at all, which is why it's easier and safer to use large items. I know that a lot of memory homes line the walls with picture frames that showcase different types of fabrics. So as you're walking along the walls, you can also move your hand along the walls. So one picture frame might have faux fur in it. One might have fleece, one might have sequined fabric.

Joe & Bella's Adaptive Apparel Collections:

Men's Adaptive Clothing | Women's Adaptive Clothing | Men's Adaptive Shirts | Women’s Adaptive Shirts | Men's Adaptive Pants | Women’s Adaptive Pants | Gripper Socks | Side Zipper Pants | Compression Socks | Best Adaptive Clothing | Adaptive Apparel